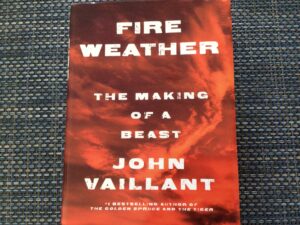

What can I say about Fire Weather than hasn’t already been said? Grim reading, for sure. Vaillant is a brilliant writer. He could not be more clear and he surely deserves every accolade he has received for this book (and more). This is one of those texts that makes science accessible to the non-scientist, like myself. If you want to understand how our exploitation of oil and gas have forever changed our atmosphere, this is the book to read.

Vaillant offers an account of the terrible fires in Fort McMurray in 2016 that saw the evacuation of an entire city. Fire Weather is almost excessively detailed, at times offering a house-by-house, heartbreaking and terrifying account of the destructive power of the fires that engulfed this northern outpost. The portraits drawn of the people in charge of the fire fighting efforts and of ordinary citizens are compelling. The fear is palpable, the losses almost inconceivable.

Irony is front and centre. Fort Mac is a city built for the express purpose of enabling the exploitation of the vast tar sands that ultimately falls victim to the destructive forces of all the carbon dioxide unleashed by the use of oil and gas. And it’s not just Fort Mac. Our whole society is dependent on oil and gas and will be undone by it.

Having lived in Alberta for a couple of decades and having a daughter who worked in the oil sands briefly as an engineer, I have an inkling of what life is like there, of what they do, of the indelible scars left on the landscape. I also know that I use products made from oil and gas every day. Our modern life is predicated on oil and gas, on plastic, on the burning of fossil fuels.

On a recent visit back to that province, I was shocked by how many people had never heard of Vaillant’s book when I asked if they had read it. Here is a “home town story” in a way, about Albertans, even heroic Albertans, a book that has been on everyone’s must read lists, a New York Times bestseller, and in my admittedly limited experience, few of the Albertans I talked to had read it or even heard of it.

But it also doesn’t matter. What happened in Fort Mac is a global phenomenon now. Maybe it is unfair to ask those most enmeshed in a deadly system to lead themselves out of it.

I’m probably wrong, but I always think change comes mostly from the outside of systems needing change. Sometimes, people with “outsider knowledge” get inside a system and try to work from there. Certainly the understanding that something is amiss is often pointed out by outsiders first. Unfortunately in this case, oil and gas companies have so much power that they can stifle almost any effort that might limit their profit. Vaillant describes how this happens in his book too, and the depth of the deception by oil and gas interests that he details is astonishing. They knew. They always knew.

I also have some limited experience with wildfire smoke. I lived in the southern interior of BC for a time and the smoke would roll into the valley every summer as the temperatures got higher and the ground drier. I know the inescapability of it. Last year, smoke seemed to be everywhere; Toronto, New York City, Vancouver. A section of Vaillant’s book had me remembering what it was like to sit in the back of my parents’ station wagon while they smoked cigarettes up front, windows rolled up. Our world is as closed an environment as my parents’ car was.

Vaillant writes, “Fort McMurray, founded at the dawn of the Petrocene Age, has grown into an unlikely flashpoint in this collision between the rapid expansion of our fossil fuel-burning capacity and the rigid limitations of our atmosphere. Here, in this city’s fire and the events leading up to it, can be seen the sympathetic feedback between both the headlong rush to exploit hydrocarbons at all costs, in all their varied forms, and the heating of our atmosphere that the global quest for hydrocarbons has initiated, and that is changing fire as we know it.” (P. 231)

In his epilogue, he writes, “The consequences of burning millions of years of accumulated fossil energy in a period of decades will be ongoing and dramatic.” He is stark in his assessments. “The willful and ongoing failure to act on climate science is unforgivable; recrimination is justified, but none will be sufficient. In this case, at the planetary level, there is no justice; the punishment will be shared by all, but most severely by the young, the innocent and the as-yet unborn.”

Yup.

Vaillant is echoing Thom Hartmann in his ground-breaking work, The Last Hours of Ancient Sunlight, a book that was formative for me in understanding what we are doing to ourselves and the planet. Maybe that’s why I see echoes of Hartmann in so many of the books I read now. We are draining the bank account of the resources the planet has stored for millennia in only a few generations. We are like drunks on a lottery-win fuelled spending spree, and we won’t stop. Won’t stop until what? Until the bottle is empty? Until the inevitable crash? Until….

In fact, it won’t stop with us. In Vaillant’s work, I begin to realize that even after our society is gone, the fires won’t stop. We have changed the chemistry of the planet and the nature of fire itself. We have fire tornadoes now. Will we leave behind a new Venus? None of us will be here to know.

Nevertheless, Vaillant tries to end on a hopeful note, invoking another favourite of mine, Hildegard of Bingen, a twelfth century nun who was able to express the regenerative capacity of our world through her combination of acute observations and her poetic soul. Maybe all is not lost. Whatever regenerates though, I surely will not be here to see it. I will have to have faith, like Hildegard.